Back in February I wrote about slop. I argued that what we call ‘slop’ is the unfortunate byproduct of widening the means of creative production. It’s a kind of runoff that pools wherever friction is low, one that accumulates when the marginal cost of producing a creative artefact converges on zero.

Since then I’ve been wondering about what slop means for visual culture. An obvious reading flows from Herb Simon’s adage that an abundance of information leads to a scarcity of attention. Slop in this sense is a pollutant that stops us from wading through the digital commons.

This is surely true, but this kind of analysis risks getting the wrong end of the stick.

At its core, the age of AI content is one where more people are able to produce creative things. Some will be good and some will be bad, but in absolute terms there will be more great art than ever.

How could there not be? We’re talking about tools that give kids in their bedrooms the same kind of firepower as a small production studio. People thought that moment was a couple of years away, but recent developments suggest shorter timelines might be more accurate.

The problem is that you have to claw your way through the sludge to get to the good stuff. All things being equal, I personally do not want to see more inane, self-referential, and stupid stuff on the internet.

Of course, all things aren’t equal. Slop is less target than collateral damage. It’s the thing that we put up with because doing so means that anyone can make stuff that was once prohibitively expensive.

The future I see is a sloppier one, but it’s also one with more good art than there has ever been before. More thoughtful films. More provocative performances. More high quality writing.

But the slop-for-creative-abundance bargain only works if you can sort the great from the good. For the deluge to be worth the price, you need to be able to reliably choose the stuff that best aligns with the type of person you want to be — and the type of person you’d like others to see you as.

You need to have good taste.

We’re going to have to paddle a little

Each new creative tool — moveable type, cheap lithography, desktop publishing or blogging platforms — has followed the same pattern. A glut of new work. Howls about falling standards. And a recalibration of what counts as good.

The lesson, if such a thing can be drawn from a study of slop across the ages, is that art gets cheaper to make over time. That lowers barriers to entry, which in turn allows more people to produce more art.

Even today, before there was ‘AI slop’ there was ‘Netflix slop’. Slop the elder can be tricky to describe, but it’s basically something like technically sound narrative emulsified for mass consumption.

Netflix is a useful thing in that it reminds us that a surplus of content creates new social worlds, but it doesn’t completely do away with the shared cultural artefacts that demarcate the ‘mainstream’.

The point is that emerging cultural touchstones maintain the capacity for making and breaking tastes. We live under the illusion that personal preferences are already unmoored from the taste of others.

Except that’s not quite true.

Yes, your X feed is not the same as mine. Your Amazon Prime recommendations look very different. But we are using the same types of viewing devices in the same familiar settings. We watch in the same kind of way.

The screen is the monoculture. It forces a shared cadence (swipe, tap, binge, skip!) even when the titles differ. That alone represents a flattening of behaviour into something we might reasonably call the mainstream.

As for what we watch, it’s true that there are a thousand shows that will never cross your path. But there are many that do, those that become a talking point in the right circles (or the basis for public policy if you live in England). These moments are thinner and faster than Dallas cliff-hangers, but they still constitute a form of mass culture.

In the broadcast age, the bundle of shared reference points that let strangers triangulate a conversation were large and stable. Today, they still exist — in that at any given moment there is a thing that lots of people are likely to know about — but its constituent parts are small and fast-moving.

Content (not to be confused with art) may already be more readily available than ever, but it’s still funnelled towards the viewer by platforms that stand in for tastemakers. You may never voluntarily watch a MrBeast video, but you still know who he is.

Subgroups flourish inside this architecture, but they are still constrained by it. Each micro-culture gets its own fifteen minutes of fame because ‘mainstream’ and ‘niche’ exist as something like phases of attention. The greater the volume of content, the more frantic the jostling for the moving middle.

Video and audio generation models will drag this process to its inevitable conclusion. There is simply no way today’s cultural settlement remains stable in a world where it’s possible to create studio-quality stuff from your bedroom. Yes, we already have YouTube, but fan-made films aren’t exactly at the same level as your average Hollywood flick.

The excess of choice will mean we can no longer ride the current and assume the best bits will wash ashore. We’re going to have to paddle a little.

In my slop era

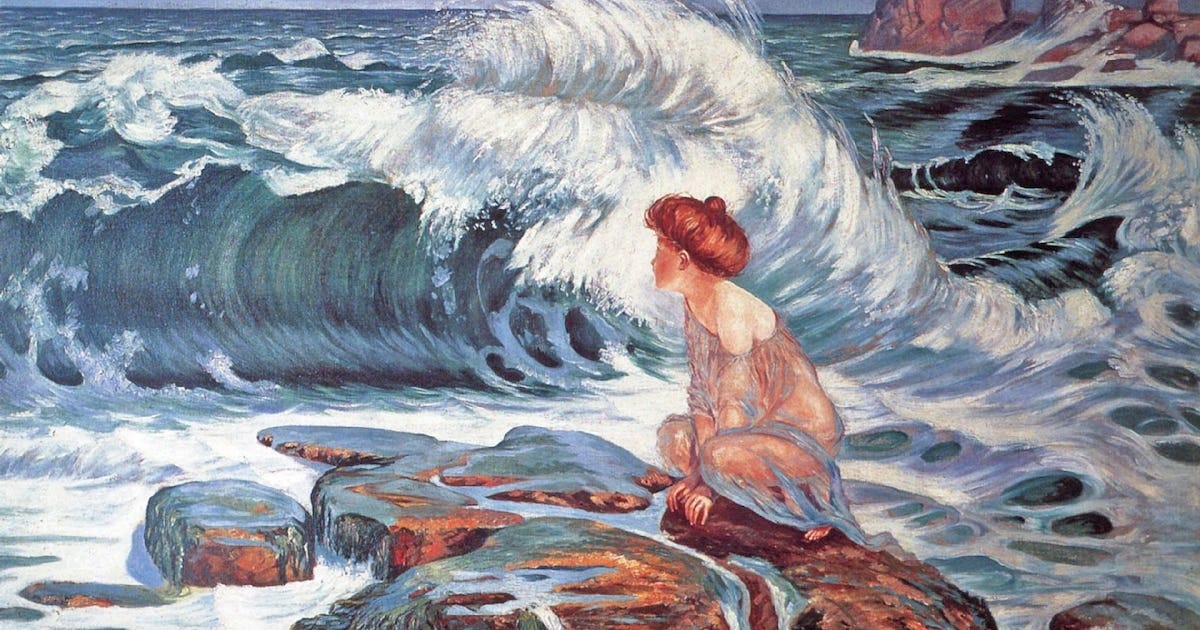

As the world gets sloppier it produces a desire for people to find the things that matter most to them. This is the impulse that is driving the emergence of the ‘tech-literature guy’, the person who is as familiar with Kate Chopin as they are with mechanistic interpretability.

People want to find steady points of reference amidst all the content. One way to do that is to revisit (or I suppose visit may be more accurate) the classics. You might begrudge the tech literature guy, but I generally think more reading is an unambiguously good thing.

Where it gets more interesting is as signal. What’s the point of reading one-thousand pages of Infinite Jest if you don’t tell anyone about it? That was important before the age of generative media, but slop has sharpened the point.

As the cost of making falls the cost of finding begins to rise. That premium breeds anxiety. Editors, commissioning boards, and gallery curators once filtered the sludge before it reached the public. Abundance overwhelms those dams and forces us to train an inner critic.

Think about it. Preference is basically a matching problem, and the profusion of AI tools creates the potential for art which is tailor-made for you specifically. That’s all well and good, but it comes with a catch: hyper-personalisation removes the last outside check on quality. Institutions, critics, and even your artier friends can’t pick the best possible option for you.

More creative artefacts will be produced. Slop will keep bubbling to the surface. The old referees will keep losing ground. But the faculty that tells you ‘this matters’ or ‘that doesn’t’ is immune to scale and indifferent to recommendation engines.

Taste can’t be automated, which is why its value appreciates in direct proportion to the noise that surrounds it. So if the age of slop feels destabilising, that’s just the weight of responsibility shifting to the individual.

I think the fixation with AI slop — and the fact that many commentators seem to completely misread what it is and why it exists — is born of anxiety. It’s anxiety about what happens in a world where the creative classes are no longer the cultural gatekeepers.

But it’s also anxiety about the need to be discerning. When there’s more to choose from then ever before, taste appreciates as cultural currency. If you’re worried about how to pick the bitter from the better, then you’re going to have a thing or two to say letting any old person make stuff and share it with the world.

90% of everything is crap (Sturgeon's Law)

This is true no matter how much of everything there is.

What changes is how much filtering we want to do and to whom we will delegate it.

Taste sounds like it is just cultural refinement but I think it’s a lot more than that. I think it’s the ability to judge for yourself. I’m actually reading Infinite Jest and I feel it’s a very challenging book on some level but it has a sharp wit to it and it has a futuristic science fiction feel that draws me in . But Wallace’s style is not for everyone. It literally is a matter of taste .