Have you watched Adolescence?

It’s a question that is part purity test and part normie chit chat. Just asking about it lets somebody know that you feel appropriately concerned about the issues of the day (or that you’re a big fan of Stephen Graham).

The great political event of the moment was top of the agenda for BBC Breakfast, when Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch was peppered with questions about her viewing habits.

In the unlikely event that someone reading this hasn’t heard of it, Adolescence is a four-part limited series about a young boy who murders a classmate after spending too long in some of the more unsavoury corners of the internet. I get why it’s been successful. The acting is good, the script is fine, and the direction solid.

But mostly it’s been a hit because its creators made something capable of psychologically one-shotting parents. Your kid’s favourite emoji is actually slang for ketamine. Their best friend sells knives. If you let them spend more than 45 minutes a day on the internet they will get red-pilled.

Back on the big red sofas of the BBC, Badenoch tries to explain that she’s too busy to watch it. But the hosts aren’t having it. There’s one particularly amusing bit where she tries to remind them that Adolescence isn’t actually real, and the interviewers shoot back that the ‘documentary [had] made much more of an impact than any politician’.

Obviously Adolescence isn’t a documentary. Even if it was, documentaries are also a flawed way of learning about the world. Or rather documentaries, like Netflix dramas, can be useful for learning stuff — just often not in the way that filmmakers intend.

That is to say: the reaction to Adolescence is much more epistemically useful than its content. So yes, while it’s strange to see the Prime Minister host the show’s creators and make it available in the UK’s schools, the breathless nature of the reaction tells us much about our cultural and political moment.

Determining the precise impact of Adolescence on the policy environment is tricky. The UK already has some of the strictest internet safety measures in the world thanks to its Online Safely Act. Adolescence isn’t likely to spur policymakers to draft new bills, but it will absolutely solidify support for laws like the OSA that already exist (something the government alluded to in a recent press release).

Imagine all the people

Policymaking is saturated with narratives, symbols, and the residue of imagination. Amongst the most well known mechanisms for making sense of these factors is Sheila Jasanoff’s sociotechnical imaginary, which describes how societies envision desirable futures.

These imaginaries are “collectively held, institutionally stabilized, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures, animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order”. More recently, researchers have argued that sociotechnical imaginaries are “unique features of political cultures that serve to define what modifications to daily life are rational and desirable.”

Imaginaries, in other words, describe what the future could look like and prescribe what the future should look like. One of the clearest accounts of how this process happens in practice involves nuclear energy.

In the early years of the Cold War, U.S. President Eisenhower’s 1953 ‘atoms for peace’ address recast the fearful image of the atomic bomb as a hopeful story about abundant energy. The canonical example of the sociotechnical imaginary, his speech “split the atom a second time” by offering a positive account of nuclear power connected to health, wealth and prosperity to offset its destructive reputation.

The atoms for peace programme legitimised increased domestic funding for nuclear R&D and provided rhetorical air cover for a diplomatic push in which the U.S. offered reactors, training, and uranium to dozens of countries. The most visible result of this work was the formation of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Away from imaginaries, the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) in policy studies provides a structured way of analysing how narratives shape policy. According to NPF, effective policy stories typically feature a recognisable setting, heroes and villains, a clear plot connecting cause to effect, and a moral that signals the policy solution.

These stories make complex issues emotionally resonant by exploiting beliefs, biases, and values. Sticking with Eisenhower, we might recall the ‘domino theory’ narrative that held that if one country fell to communism, its neighbours would soon follow. As Ike put it:

Finally, you have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the "falling domino" principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.

Such narratives are information-dense. As Paul Cairney notes, policymakers use stories and metaphors as a form of cognitive management in response to time and knowledge constraints.

Ideas like atoms for peace or domino theory perform two important functions: they contain larger models for making and breaking policy, and sustain simplified readings that can win or maintain public support.

The second half of this post contains two short case studies about the uses and abuses of fiction in policymaking. The first deals with the impact of a single artefact on decision-making, while the second explores the formation and stabilisation of meta-narratives.

The Day After

In 1983 American TV network ABC aired The Day After.

The film, which vividly depicted the outbreak of nuclear war and the post-apocalyptic devastation in an American town, notched up 100 million viewers on release. President Ronald Reagan screened The Day After at the Camp David presidential retreat, writing in his diary that it was “very effective & left me greatly depressed.”

The Day After was a product of the Cold War. In September 1983 the USSR had shot down a Korean airliner with air to air missiles, which took with it 269 passengers including a contingent of U.S. Congressmen.

Shortly afterwards a suicide bomber destroyed a U.S. barracks in Lebanon, and Reagan ordered the invasion of Grenada to install a favourable government as part of America’s ongoing contest with the Soviet Union.

Two knife-edge moments came in the closing months of 1983. In September, Soviet early warning systems alerted staff to what were thought to be incoming U.S. warheads. A duty officer famously ignored protocol and the missiles proved to be a computer glitch caused by solar activity.

Two months later the Able Archer war games in Europe led to what the National Security Agency described as “the most dangerous Soviet-American confrontation since the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

Reagan watched The Day After in the period between these two crises. After his screening at Camp David, senior military staff explained in excruciating detail what the likely aftermath of nuclear exchange would look like.

As Reagan recalled, the meeting was “the most sobering experience…in several ways the sequence of events parallels those in the ABC movie…that could [lead] to the end of civilization as we know it.”

By early 1984 Reagan’s speeches had taken on a very different tone. Ahead of a disarmament conference held in Stockholm, the president mentioned ‘peace’ in a landmark speech no fewer than 25 times:

1984 is a year of opportunities for peace. But if the United States and the Soviet Union are to rise to the challenges facing us, seize the opportunities for peace, we must do more to find areas of mutual interest and then build on them.

Clearly we can’t say that The Day After was primarily responsible for the detente. The point isn’t that the film represents an essential moment in Cold War history, but rather that it gives us a straightforward example of the potential for fiction to radically influence policy.

It reminds us that policymakers don’t just create fictions, they actively consume them. Sometimes a piece of media influences them directly, but more often than not powerful fictions are harder to pin down.

‘Video nasties’

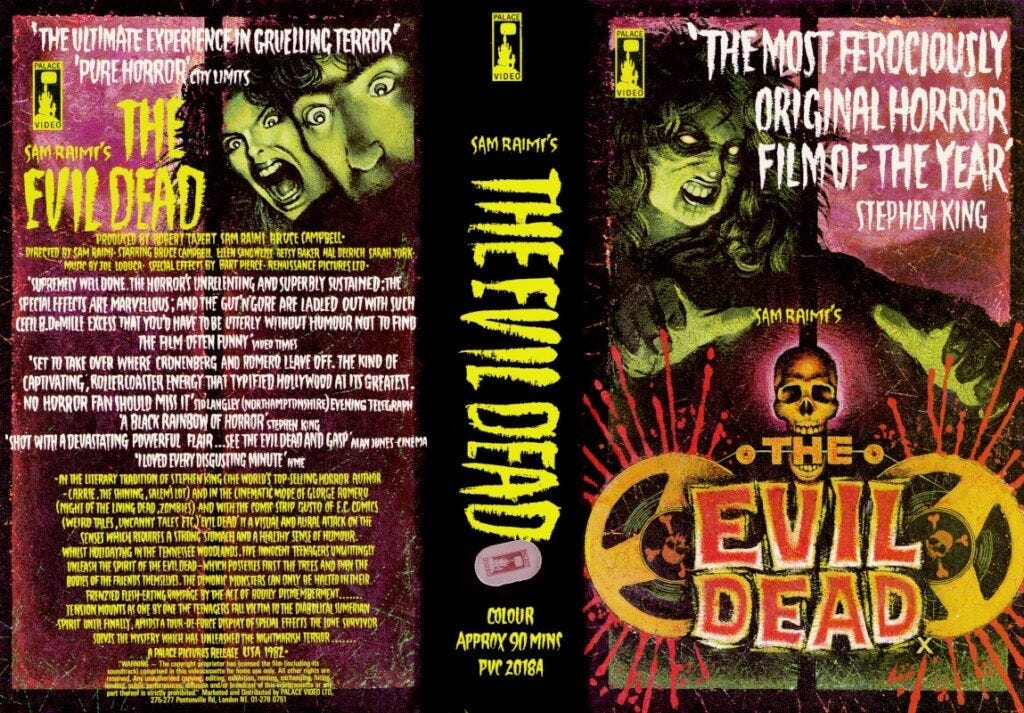

Take Britain’s ‘video nasties’ craze of the 1980s.

Far away from the high drama of the Cold War, the UK government was also wrestling with the influence of fiction on policymaking in 1984. It was a year in which parliament passed the Video Recordings Act, which saw the establishment of a British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) responsible for the certification of both cinema and video releases.

While that sounds fair enough, in practice the bill was horribly draconian. Because home video classifications carried legal force (unlike classifications for cinema films) it became a criminal offence to distribute, rent or sell an unclassified video. The BBFC could refuse certification on subjective grounds, which meant that huge numbers of films became illegal to own.

The Video Recordings Act started life as a private members bill in response to the circulation of low rent horror movies made available on VHS tape. Conservative MP Graham Bright, the sponsor of the bill, famously called the tapes ‘video nasties’ and demanded action to ban them.

So did huge chunks of the UK press. A year earlier the Daily Mail launched a campaign with the front-page headline “Ban video sadism now,” which attacked home secretary William Whitelaw’s unwillingness to contemplate statutory regulation as “ludicrous”.

In the same year Mary Whitehouse, founder of the National Viewers and Listeners Association pressure group, wrote to all UK MPs asking for support to ban horror films. Around 150 replied that they would back video legislation if introduced in the House of Commons. A bill was quickly spun up and quietly passed to Bright to introduce as a private members bill to avoid the need for third party consultations.

The text passed with practically no serious opposition, benefitting from what the historian Chas Critcher described as a ‘moral panic’ (an overused term that is appropriate in this particular instance).

A core property of a moral panic is convergence, which the cultural theorist Stuart Hall said occurs when “two or more activities are linked in the process of signification so as to implicitly or explicitly draw parallels between them.”

What he was describing was a process in which seemingly not-so-bad-thing (A) becomes entangled with obviously-bad-thing (B). Many column inches and think pieces later, a harsh policy for thing (B) also looks like a positively sensible move for dealing with thing (A).

Much like social media, ‘video nasties’ were thought to be responsible for just about every social ill you could imagine. In an excellent review of the episode, Julian Petley explains that despite practically no evidence the press connected the tapes to:

Sexual violence: Recurring images in media accounts involved rape, mutilation, and torture, particularly of women. Reporting suggested that titles like I Spit on Your Grave and SS Experiment Camp normalised such behaviour.

Stunted emotional development: Widespread claims that a) many children were watching these films and b) this was damaging their development. Politicians and campaigners said videos were “raping children’s minds.”

Murder: High-profile criminal cases were linked to supposed copycat behaviour, with courts and newspapers blaming The Driller Killer and The Last House on the Left for acts of violence.

Moral decline: The videos were cast as symbols of a broader decay in British values. Deemed to be especially important under the Thatcher government's campaign for the restoration of lost social norms.

Organised crime: Tabloids described video distributors as “gangsters” profiting from “evil pornography,” which fed fears of the tapes being used to support sophisticated criminal networks.

Finally, like all great British political controversies, class was in the air.

In a 2014 article The Independent reported that, after a screening of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for British Film Institute members, BBFC head James Ferman said: “It’s all right for you middle-class cinéastes to see this film, but what would happen if a factory worker in Manchester happened to see it?”

Useful fictions

Metaphors, narratives, and imaginaries are slippery by nature. We know that movies can influence decision-makers directly, yet one doesn’t even need to watch a film for it to alter the contours of the policy environment.

This observation partly explains why a TV show can handily win hearts and minds. It exerts influence at the top through policymakers and below via pressure groups, the press, and various other publics.

Many fictions are useful, but some are more useful than others. Adolescence has been so successful because it manages this kind of dual articulation. It’s both The Day After and video nasty.

I don’t think this kind of traction can be planned. Much has been made of state funding for the studio behind the show, but I suspect that is trying too hard to pattern match.

In fact, I imagine the opposite is true. We know that fictions can take on a life of their own. They are powerful but difficult to wield, once you release them into the wild who knows where they will end up.

In art as in life, anything can happen if the story is good enough.