It’s 1894 in the city of La Coruña on Spain’s northern coast and José Ruiz y Blasco is painting a pigeon. He steps away from his easel for a moment, but when he comes back his thirteen-year-old son has finished the job.

The boy is good. Very good. So good that his father stops dead in his tracks. Ruiz had been painting birds for years. He was a trained artist, a respected professor at the city’s School of Fine Arts. He knew technique when he saw it, and resolved to give up painting when he thought his son had surpassed his old man.

The boy is Pablo Picasso, the great Spanish artist who liked to remind us that ‘art is a lie that makes us realise truth.’

The anecdote isn’t completely true — there are later paintings attributed to Ruiz — but the episode still gets remembered as a particularly resonant origin story in the art history canon.

Picasso built his reputation on rejecting naturalistic representation. He pushed Cubism into the cultural imagination because he knew that literal depictions of reality were a fool’s game. Instead, the Spaniard spent the best bits of his career celebrating how futile it is to show things as they appear to be.

And yet the story we tell about his youth is one of technical mastery. It’s about a bird rendered so perfectly that it convinced a professional painter to put down his brushes for good. Maybe the myth is necessary. Perhaps we need to believe Picasso could portray the perfect pigeon before we accept that perfect pigeons aren't worth the paint.

Then again, the young Picasso’s work wasn't actually flawless. It couldn't be because reality is infinitely complex and infinitely temporal. Any attempt to represent it is by definition an act of reduction. All paintings, no matter how detailed, exist in the margin between the thing and someone's attempt to show it to us.

In this sense, art is error.

For those of us interested in the AI project, it’s an idea that explains why some generative art looks kitsch or banal. When Midjourney produces images indistinguishable from a National Geographic photography exhibition, we get technical proficiency that rings hollow.

Yes, as models become more sophisticated they get better at representing reality. But that doesn’t get anyone’s blood pumping because the gap between what is and what we see can never be fully closed. It’s for this reason that the wise artist embraces the space between, rather than pretending it doesn’t exist.

Beautiful errors

A few years ago I went to the Vatican. It’s a good day out, so long as you have nothing against metal detectors or being herded from one room to the next like cattle. Michelangelo’s ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is especially wonderful, mainly because it’s big enough (and far away enough) to be seen from deep within the crowds.

If you wriggle past the tour groups you might steal a glimpse at Raphael’s School of Athens, that monument to Renaissance idealism where each figure exists in exquisite harmony. Every line of perspective is satisfyingly calibrated and every face an expression of classical beauty.

The School of Athens depicts neatly proportioned bodies whose classical beauty is itself a kind of fiction. We still look at it because Raphael’s ‘perfection’ is a meaningful departure from reality, one that shows us a vision of human potential and intellectual harmony.

Alas, even error can become stale. What felt revolutionary in one generation becomes formulaic in the next. By the 19th century, Raphael's particular way of getting things wrong had been copied and systematised into predictable beauty.

What began as revolutionary techniques for representing reality became formulas for perfecting it. High art grew technically proficient but emotionally flat. Students copied masters who copied other masters, eventually creating a hall of mirrors that reflected the same forms.

Art needed new kinds of meaningful mistakes.

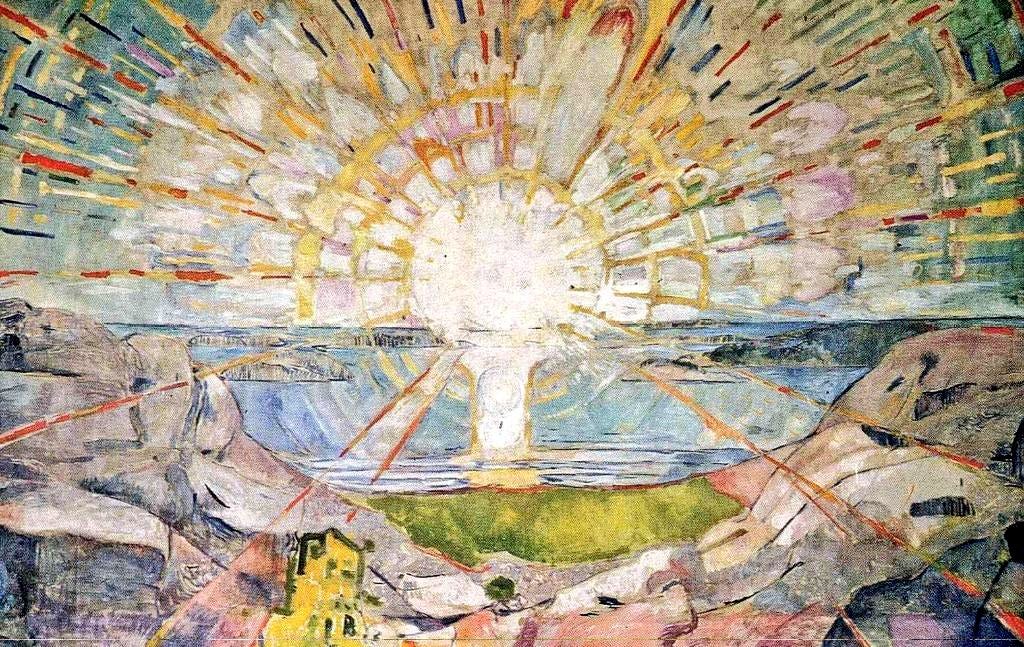

Every creative movement that mattered was a rebellion against the world that came before it. The Impressionists abandoned linear perspective for fleeting light. The Expressionists distorted faces to show emotion. The Dadaists threw coherence out the window by embracing absurdity as their organising principle.

Each of these groups recognised that art mediates between intention and execution, between what we can see and what we can depict. Close that gap too fully and you have something closer to documentation than art.

Every representation departs from reality in some way, but there are two very different approaches to dealing with that withdrawal (discounting attempts at accurate depiction). You can try to fix reality's messiness by smoothing away its imperfections in pursuit of beauty. Or you can amplify the world’s strangeness, pushing departures further until they reveal something that literal representation cannot.

Classical art tries to hide artifice by making its idealisations feel natural and its corrections inevitable. Revolutionary art celebrates deficiency, encouraging the viewer to reckon with the distance between reality and representation.

Picasso did the latter. In 1907, he produced Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, a painting that critics initially dismissed it as the work of a madman. Faces twisted into geometric fragments. Bodies viewed from multiple angles simultaneously. Colours that clash and lines that unsettle.

What Picasso saw — and what would define modern art for the next century — was that error could be the point. The mistakes that classical artists spent lifetimes learning to avoid could be reimagined as new ways of seeing.

The Surrealists had figured this out too, though they approached it from the opposite direction. Salvador Dalí’s paranoiac-critical method involved deliberately inducing a state of delusional perception, staring at random objects until he tapped into the ‘symbolic language’ of the subconscious mind.

René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, which famously shows a pipe with the caption ‘this is not a pipe’, forced viewers to confront the fiction of representation. The idea is that these words make us conscious of the membrane between rendition and reality.

But it was the Cubists who gave us the most systematic approach. The likes of Georges Braque and Juan Gris formalised a new visual grammar based on fragmentation. Unlike previous movements that rebelled against specific techniques, Cubism rejected the fundamental premise of Western art since the Renaissance: that painting should create the illusion of looking through a window at reality.

Cubism was about information density. By deliberately breaking perspective, its painters could pack more knowledge into a single image than a camera could capture. They thought that art should convey our accumulated knowledge of something, not just a single encounter with it. This is partly what Picasso was getting at when he said ‘I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them’.

The golden age of broken AI

I bought this painting in 2019. It looks like a classical allegory, but with a flatness that reminds us we’re looking at the work of a machine. The faces are clearly human, but impossibly so.

It was produced by a generative adversarial network, a system in which two neural networks are locked in competition. One network (the generator) tries to create images convincing enough to fool its opponent, while the other (the discriminator) evaluates and scores the generator's output, pushing both to improve through competition. You can think of them as artist and critic.

GANs can be used for generating synthetic training data and detecting deepfakes, but they're known by most people as the class of models that brought AI art into the public imagination (there was of course Deep Dream, but it was a little more contained to the extremely online amongst us).

Early generative adversarial networks couldn't paint a convincing human face, but they could create portraits that existed in the uncanny valley between recognition and abstraction.

A GAN that learned to associate ‘face’ with certain patterns would dutifully reproduce them, even as the result looked like an acid trip. The machines were trying their best to paint like humans and failing, but the result was often better than they have any right to be.

We crossed a threshold somewhere between the flowing figures of early GANs and the hyperreal perfection of modern diffusion models (the things that make ChatGPT’s image generation function tick). The machines learned to stop making interesting mistakes by default. They became too competent and too reliable.

Early GAN outputs were obviously artificial, but they were more than synthetic slop. Compare that to your average image model today. In producing work that is too polished, they trigger a kind of emotional flatlining where we recognise a solid simulation and respond with indifference.

The labs have built systems that can render skin texture with exactness and generate lighting that obeys the laws of physics. Composing images according to the classical principles of beauty is for them light work.

But good art rarely tends to be so neat. Early image models were interesting because the machines had a thing for category errors. They saw features in noise, mixed up spatial relationships, and whipped up impossible architectures that felt emotionally satisfying.

Picasso spent his career learning classical techniques so he could break them. The best AI artists do the same thing by understanding how these systems function well enough to make them work poorly in the right ways.

Even in widely available image generators the tools are already there. Sliders that control how closely the model sticks to the prompt. Seed values that determine which accidents occur. Negative prompts that can force models to avoid trained behaviours.

Every AI system contains the germ of its own rebellion, if we're clever enough to cultivate it.

The most honest AI art puts artificiality to work. Images that look machine-generated but use aesthetic distance to reveal truths about its subject, or texts that sound alien but illuminate aspects of language we take for granted.

Glitch artists have been doing something like this for a long time. What they did with early digital systems, we can do with transformers, diffusion models or generative adversarial networks. The key is carefully orchestrated failure that reveals patterns invisible to conventional seeing.

I’m glad the systems got better, but I’m disappointed that the default way of using them emphasises their ability to accurately model reality. It should go without saying that there are plenty of artists who already use AI thoughtfully in their work, but the point is that the average user is drawn to faultless representation rather than beautiful error.

Instead, we ought to remember that there is no such thing as a perfect picture. Not for the ancients, not for the modernists, and not for us. Better to recognise that art lives between reality and perspective, and that the gap is where the good stuff happens.