Emily Dickinson paid attention.

The American poet, who lived most of her life in near-seclusion in New England, wrote nearly 1,800 verses. The collection is about the small stuff. The slant of afternoon light, the tremor of breath, a blade of grass minding its own business.

Dickinson’s work shows us that the world is ripe for remaking. In many of her untitled poems, she rearranges a profound moment around a tiny slice of the ordinary. In one well-known example, Dickinson writes that the last thing one unfortunate subject hears is the buzz of a fly’s wings before their soul leaves their body:

I heard a Fly buzz - when I died -

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air -

Between the Heaves of Storm -

The fly reminds us that the mind has a mind of its own, that even the important bits sometimes play second fiddle to the things that shouldn’t matter. That’s the power of attention, the thing that lets us make our own worlds and live inside them.

Attention has been a spotlight, a filter, a resource, and a currency. It’s a shape-shifting concept that connects monks and mindfulness to search engines and self-driving cars, one whose latest afterlife is a mechanism for information processing.

Take an image recognition system like a convolutional neural network (CNN). A CNN works by sliding small filters, which you can think of as screens, across an image. At each step, the network activates certain neurons when a particular feature is detected (like edges or textures) while ignoring others.

Each cluster of neurons responds to only a portion of the whole picture. With enough layers, these local features are combined into more abstract representations: a curve becomes a nose, a circle becomes an eye, and eventually the system recognises a face.

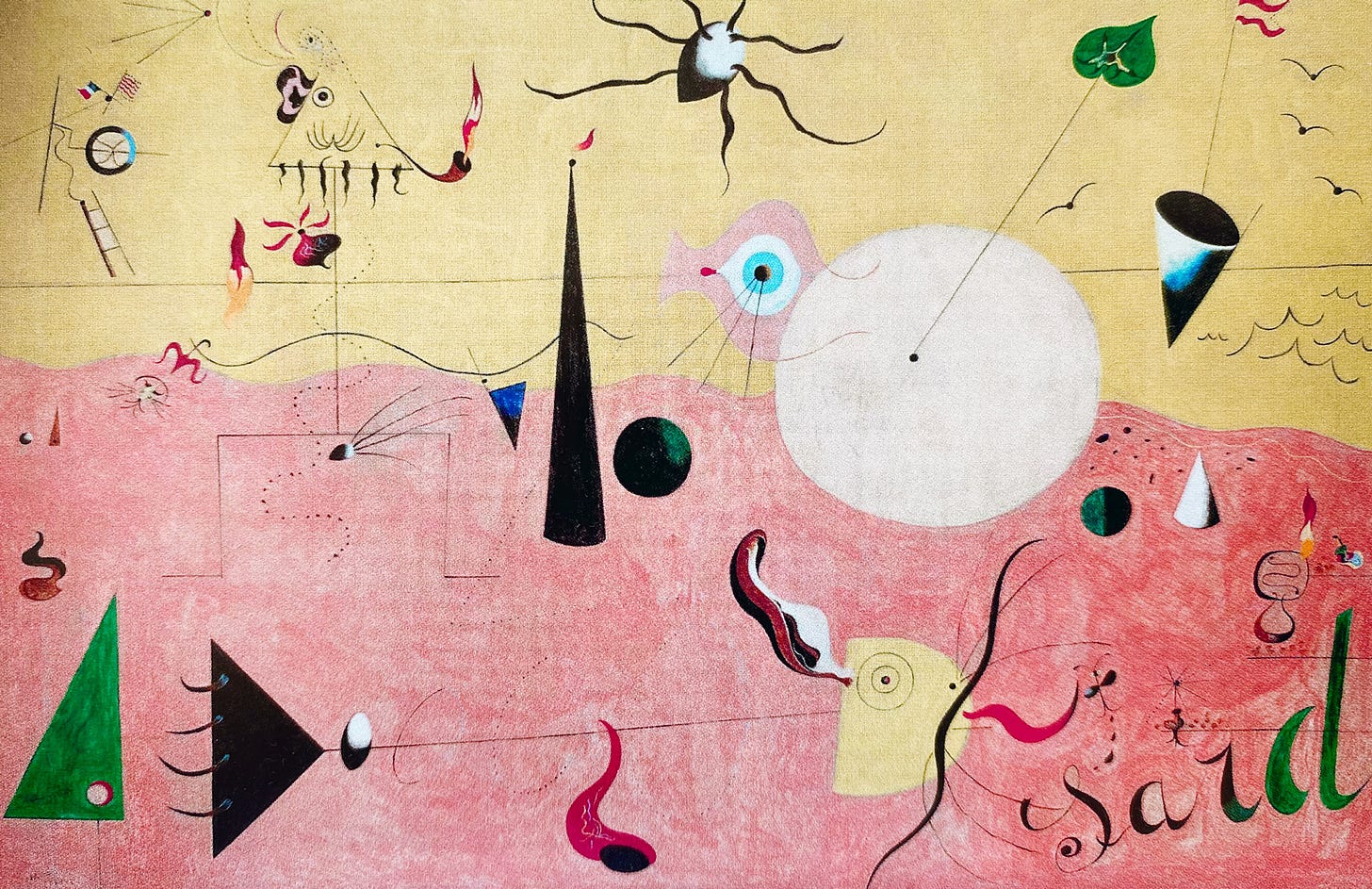

In machine learning as in the brain, understanding is compositional. We can’t attend to everything at once, so we choose to work locally. We obsess over a paragraph, a turn of phrase, or a figure in a painting. The more intense our focus, the more meaningful the pattern.

The literary critic I.A. Richards called this style of analysis 'practical criticism’. Richards gave poems to students without any contextual clues, reporting the results of a 1929 experiment designed to encourage focus on 'the words on the page' rather than preexisting beliefs:

For Richards this form of close analysis of anonymous poems was ultimately intended to have psychological benefits for the students: by responding to all the currents of emotion and meaning in the poems and passages of prose which they read the students were to achieve what Richards called an 'organised response'. This meant that they would clarify the various currents of thought in the poem and achieve a corresponding clarification of their own emotions.

Richards’ approach relates to the idea that knowledge is situated. An important bit of the science and technology studies canon, the point is that one can never see the whole system — only a perspective within it. All vision is partial perspective.

That is true for people, organisations, and systems. It’s also true for scientific discovery, a point made clear in Thomas Kuhn’s famous work on the formation and stabilisation of scientific paradigms. We might say that pre-paradigmatic science is chaotic, but once we get a filter (in this instance, a scientific framework) we start to see things that we couldn’t before.

Paradigms are ways of selectively attending to data. They obscure the full picture so we might see more clearly, all the better to help us sort signal from noise. Like image recognition systems or Dickinson’s poetry, paradigms work because they pay attention to the right things.

Divining attention

Attentive awareness goes back some. One could credibly make the case that it allowed early humans to make meaning and abstract the world around them in useful ways. After all, the hunter-gatherer’s life depended on noticing the flicker of prey in the undergrowth, subtle shifts in the wind, and tracks barely pressed into mud.

In the long run, the ability to focus supported the emergence of complex rituals, artistic practice, and forms of mysticism. The French anthropologist Marcel Mauss said that ‘underlying all our mystic states are corporeal techniques, biological methods of entering into communication with God’.

William Golding’s novel The Inheritors deals with the collision between homo sapiens capable of selective attention and Neanderthals who live moment to moment. While the book anachronistically gives homo neanderthalensis religion, it does a wonderful job at describing how beings with limited attentive capacity might have made sense of the world.

Attentive practice and mysticism became more important as humans traded hunting for agriculture. In ancient Egypt, priests observed the movements of stars and sacred rites with exacting focus. They believed that attention maintained the balance between order and chaos.

In the Vedic traditions of early India, attentiveness underpinned the meditative practices aimed at perceiving the hidden unity of Brahman, the ultimate reality. Across the Mediterranean, the mystery cults of Orphism taught that salvation depended on vigilant self-awareness during life and death.

Ancient Greek philosophy eventually developed its own form of contemplative vigilance. The Stoics called it prosoche, a steady stream of active attention for living in accordance with the rational logos that pervades the cosmos. To attend was to consciously participate in the divine structure of reality.

Early Christian monastics saw attentio (or nepsis, meaning ‘watchfulness’) become a virtue. The first generations of Desert Fathers, a group of ascetics who lived in Roman Egypt, singled out attentiveness as a fundamental Christian moral quality. For the Desert Fathers, prayer itself was a pure form of attention to the divine.

On the other side of the world, Buddhist contemplative traditions fashioned the training of attention into a sophisticated discipline. The Buddha’s teachings about mindfulness (sati) and concentration (samādhi) can be read as prescriptions for holding one’s attention in the present.

Like their Buddhist counterparts, the desert ascetics emphasised lived practice over theoretical knowledge. One trained attention through recitation of the psalms; the other used the sutras. Both traditions recognised that verbal practice served as scaffolding for attentional states.

These traditions understood that the untrained mind wanders endlessly, and prescribed attentional discipline as the antidote. Desert Father Abba Moses’ advice to ‘sit in thy cell and thy cell will teach thee all’ sounds eerily similar to the Buddha's emphasis on solitary meditation as a vehicle for insight.

By the early Middle Ages, attention began to look something like a formalised discipline. What had once been the preserve of solitary ascetics or wandering monks was pulled into the orbit of the institutions that governed religious and intellectual life.

In the monasteries of medieval Christendom, attentiveness became a rule-bound discipline, essential for the copying of sacred texts. In the Islamic world, scholars preserved and systematised ancient knowledge through attentive reading and commentary. Across Europe, the rise of Scholasticism gave new life to on ordered training of the mind and the belief that attentiveness lit the path towards divine truth.

The Italian priest Thomas Aquinas treated attentio as a crucial operation of the soul, the means by which intellect and will could be properly directed toward God, truth, or moral goods. Paying attention was to marshal scattered faculties into a disciplined focus. It was in some ways a rational act, one that represented victory over the unruly appetites that tempted the soul.

This rational-ish style of attention gradually evolved into an intellectual virtue at the heart of Renaissance humanism. Scholars like Erasmus urged readers to cultivate active attentiveness in an age when the printing press flooded Europe with classical and scriptural texts. To read well was now to sift wisdom from error, to attend to meaning rather than memory.

Erasmus urged readers to dwell, discriminate, and refine the mind through the careful discipline of reading and thinking. A century later, Descartes pushed the logic of attentiveness further by arguing that attentive scrutiny was the foundation of certainty.

His method of doubt, famously outlined in Meditations, demanded a focusing of the mind’s gaze away from the noisy flux of the senses and towards only those ideas that could be grasped with absolute clarity. Once spiritual and later humanistic, attention was becoming the instrument by which knowledge could be assembled from the ground up.

In the eighteenth century, Immanuel Kant built on Gottfried Leibniz’s concept of apperception, which deals with how the mind becomes aware of its own perceptions, to argue that coherent experience depends on the active work of the mind. For Kant, the mind bound perceptions together into a unified world through an original act of synthesis.

Kant is an important figure in our narrative because he shifted the philosophical terrain from the contents of thought to the structures that made thought possible. It might sound a bit niche, but this distinction encouraged others to view the mind as an active organiser of experience rather than a passive receiver of impressions.

Rethinking attention

Wilhelm Wundt founded the first psychology lab in 1879. As a young man, the German struggled with nervousness and daydreaming. He was reportedly prone to losing focus and drifting into reverie.

Wondering why he struggled to stay on track, Wundt set about to study the psychological dimensions of attention. He began with Leibniz’s apperception, which he treated as the voluntary direction of attention by which sensations were selected, organised, and made conscious.

Wundt was a Kantian in that he believed that experience depends on the active organisation of perception. But where Kant had treated this as a necessary and universal structure of mind, Wundt focused on the elective aspects of attention. He wanted to know how we selectively direct focus, how we amplify or suppress sensations, and how these choices could be measured experimentally.

Around the same time, physicist-turned-physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz performed a simple but important experiment. Fixating his gaze on the centre of a briefly illuminated array of letters, he found that he could covertly shift his attention to a different part of the array. Helmholtz could make out letters in this region while the rest remained a blur.

The central insight was that attention could act independently of eye movement. Attention, as it turned out, was a distinct cognitive faculty, one capable of selectively enhancing experience from within.

Around a decade later, William James confirmed attention’s role in the new psychology. In The Principles of Psychology (1890), James described attention as the mind’s act of taking ‘possession of one out of what seem several simultaneous objects or trains of thought’ emphasising that ‘focalisation, concentration, of consciousness are of its essence.’

He argued that focus is a process of active selection, one that ‘implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.’ For James, attention was the essential mental act. It made order from chaos, clarity from confusion, and identity from experience.

James had placed attention at the heart of mental life, but within a generation, psychology’s centre of gravity had shifted. In the early twentieth century, the rise of behaviourism relegated attention to the margins of scientific respectability. Figures like John B. Watson insisted that psychology must concern itself only with what could be directly observed, namely external stimuli and behavioural responses.

In line with the new paradigm, attention was redefined as the observable orientation toward certain stimuli rather than others. The idea of attention as an active, inner force shaping consciousness—so central to Wundt and James—all but disappeared for several decades.

But it wasn’t to last. A new generation of researchers argued that psychology could not make sense of complex phenomena like language, reasoning, or memory without grappling with internal mental processes.

Known as the cognitive revolution, this movement reimagined the mind as an active processor of information capable of selecting, storing, retrieving, and manipulating inputs much like a computer. In this new framework, attention returns as a central object of study. No longer dismissed as unmeasurable, it was now seen as a mechanism for managing the mind’s limited processing capacity.

Psychologist Donald Broadbent gave the new cognitive psychology one of its first working models of attention. In 1958, drawing on wartime research with pilots and radar operators, he proposed that the mind uses an early-stage filter to manage the flood of incoming information. Like a gatekeeper at a switchboard, Broadbent hypothesised that an attentional filter allows one stream of sensory input through for conscious processing while blocking the rest.

This neatly explains why, when listening to two people speak at once, we can follow one conversation and tune the other out. Broadbent's model was crisp and mechanical, treating attention as a bottleneck tuned to a selected channel. It was elegant, and for a time, dominant — but brittle.

In certain listening studies, participants could sometimes pick up personally relevant information like their own name in an unattended conversation. This suggested that unattended material was not completely blocked. Another experiment went further, demonstrating that people could unconsciously piece together meaningful phrases from words split across different audio channels.

Building on these tests, English psychologist Anne Treisman proposed that attention was not a screen so much as a volume control where unattended inputs were weakened but not completely eliminated. Meaningful information could still break through if it crossed a certain threshold of relevance.

Treisman later turned her hand to visual perception, developing what became known as Feature Integration Theory (FIT). She showed that basic features like colour, shape, and orientation are first registered automatically (and separately) by the visual system.

The theory held that without attention the brain can conjoin features incorrectly— seeing, for instance, the colour of one object attached to the shape of another—in a phenomenon known as illusory conjunctions. According to FIT, attention was a necessary process for binding separate features into coherent perceptual objects. Without it, the visual world would fragment into disjointed colours, shapes, and patterns.

During these decades, psychologists began to develop new metaphors to capture how attention behaves. Michael Posner famously likened attention to a movable ‘spotlight’ that selectively enhances processing wherever it points. Others proposed a ‘zoom lens’ model suggesting that we can widen or narrow the scope of our focus by trading breadth for resolution.

The metaphors masked a deeper shift. Attention was less static filter than dynamic resource that the mind could steer, widen, or narrow. In the cognitive view, attention was an active force that regulated the flow of information moment by moment rather than holding focus behind a single gate as in Broadbent’s model.

Daniel Kahneman carried forward the interpretation of attention as an active process, but reframed it in terms of limited mental resources. In his 1973 book, the great psychologist likened attention to a finite pool of energy that could be allocated flexibly across tasks. Performing two tasks at once was difficult if they drew heavily on the same attentional reserves, but easier if one was automatic or if they tapped different cognitive systems.

By the late twentieth century, attention could be seen at work. New techniques like the electroencephalogram (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) allowed researchers to connect attention to brain activity. Neuroimaging studies identified regions like the intraparietal sulcus and the prefrontal cortex that acted as ‘searchlight operators’ that directed focus and regulated the flow of information.

Neural data suggested that attention was not a single mechanism but a collection of related processes like orienting to stimuli, filtering out distractions, sustaining focus over time, and switching flexibly between tasks. Attention had become a material process, one that would influence technology and our relationship with it.

Mechanising attention

Herbert A. Simon, a giant in the history of AI, said that ‘In an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else…what information consumes is the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.’

For most of human history, information had been scarce and attention plentiful. Now, information was everywhere, and attention had become the limiting factor. In their 2001 book, The Attention Economy, Thomas Davenport and John Beck argued that this shift was creating a new kind of economy in which value was measured by the ability to capture and hold human attention.

The attention economy concept, though related to the psychology of attention, is not identical to it. In cognitive science, attention describes the selective processing of information under conditions of limitation. In the marketplace, attention is measured externally through clicks, views, and time spent.

The brain’s limits turn attention into a zero-sum resource. Over time, psychological findings about attention—its spans, its bottlenecks, its failures—have been absorbed into everyday language. What was once a description of mental effort has become a common framework for parsing a mode of living under the weight of information.

There are of course two parts to Simon’s famous quote. We all remember the bit about attention, but what may prove more significant is the sheer volume of information being produced. He didn’t know it then, but information would become the raw material for a new generation of machine learning systems inspired by attention itself.

In the mid-2010s, machine learning researchers began using the term ‘attention mechanism’ to describe a method for selectively processing information. Rather than treating all inputs equally, these systems could focus on the most relevant parts of the data. Dzmitry Bahdanau, Kyunghyun Cho, and Yoshua Bengio introduced the first influential version of this idea in neural machine translation, allowing models to dynamically align with specific words in a source sentence as they generated translations.

Instead of compressing an entire sentence into a fixed representation, Bahdanau’s model saw the system search through the source sentence during translation. The model could attend to different parts of the input at each step, much as a bilingual speaker might glance back at the original text to refine a translation.

But the major moment for attention, as all AI watchers know, came in 2017 when Google described the transformer architecture built around the famous self-attention mechanism. Where Bahdanau’s model used attention to improve a sequential system, transformers opted to discard recurrence altogether. Instead of processing information step by step, the architecture used multiple attention mechanisms in parallel to compare every part of the input to every other part at once.

In a transformer, every word in a sequence can attend to every other word through learned weightings. For each word being processed, the model calculates attention scores between that word and all words in the input. It basically asks ‘How much should I pay attention to word X when processing word Y?’

This approach yields an attention map that tells us which parts of the input are most relevant to each word being processed. By using many heads that each focus on different aspects of the input, the model can pick up multiple kinds of relationships at once such as syntax or semantic context.

The result is a rich representation of language (and as it turns out, probably a lot more than that). To put it simply, language models amplify important signals and suppress less important ones. Their use of attention has even prompted loose comparisons to the way neural circuits in the brain manage focus and selection.

That isn’t to say that language models are brains, but rather that the convergence between the two reflects shared constraints if not a shared nature. Faced with too much information and finite processing power, both minds and machines must solve the same underlying problem: how to select what matters.

Attention is a product of limitation. Whether in the prayers of ascetics, the experiments of early psychologists, or the designs of machine learning engineers, the problem is the same. It’s the one about how to find coherence in a world made up of more than can be grasped.

If the story of attention tells us anything, it’s that all seeing is partial. The mind knows by focusing. Science progresses by filtering. Machines learn by selecting. No perspective, human or otherwise, can capture the whole. To attend is to miss almost everything, but that’s the whole point.

Emily Dickinson once wrote that ‘a letter always feels to me like immortality because it is the mind alone without corporeal friend.’ What she meant was that letters offered a way for the mind’s expression to endure on its own, that they exist as fragments of the self that outlast the living.

In her poems, attention works in much the same way. A single moment, chosen and held, becomes a whole world. The mind’s spotlight falls where it falls, whether on the wings of a fly, a band of light, or a blade of grass.

Attention is not what limits our experience of the world. It’s what makes experience possible at all. Without the narrowing there would be no coherence, no meaning, and no world to perceive.

As someone who grew up reading world poetry, philosophy and modern classics - really admire this piece! I'll have to read this slowly and perhaps listen to it (a few times).