Arthur Conan Doyle sat in a dim Edinburgh library pouring over medical texts. In the winter of 1880, long before Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson captured the imagination of Victorian England, the young writer was a student of medicine — not fiction. As Conan Doyle would have it, his reading was interrupted by a friend who asked whether he’d take up a position as a surgeon on a whaling ship bound for the Arctic. He accepted, and within a week was on his way north.

In his diary, he speculated that an ancient city of Greenland existed behind the ice inhabited by the descendents of Norse settlers. Are they, he wrote, ‘still singing and drinking and fighting’? Or had some terrible fate befallen the Norse people who once called Greenland home?

The genesis of the lost tribe goes back to the 10th century. According to the Saga of the Greenlanders, the first Norse settlement was founded by Erik the Red — a Norwegian colonist of Iceland who was banished from his new home for bad behaviour. Heading west, Erik eventually found a huge island with smatterings of good pastureland.

Returning to Iceland, he drummed up support by calling the new territory ‘Greenland' as something like a medieval PR stunt. The name caught on. Over the coming years, the population of the colony swelled to between 2,000 and 3,000 people at its peak.

Then they vanished.

News from the settlements, once the northerly edge of the European world, gave way to an eerie silence after 1410. While modern archaeology confirmed that the colonists disappeared over the course of decades, it’s unclear what exactly happened to them.

Until the 20th century, scholars and storytellers alike wondered whether their progeny still inhabited the land. Names were to blame. Some old texts described an ‘Eastern Settlement’, which actually existed on the western side of the island. Because icy conditions make the eastern shore particularly inaccessible, the curious could only guess what lay on the other side of Greenland.

Resolving to find out, Scandinavia returned in force some 300 years later. The modern colonisation of the island began in 1721, when the missionary Hans Egede landed in Greenland. Egede found no Norse colonists, but he did make contact with the Inuit population (who were thought to have migrated there around 1300). Egede described a conversation with the Inuit in which they said the Norse colonists fought bitterly with coastal raiders until they were eventually undone.

“A year later, the evil pirates returned and, when we [the Inuit] saw them again, we took flight, taking some of the Norse women and children along with us to the fjord, leaving others in the lurch. When we returned in the autumn to find some of them again, we learned to our horror that everything had been pillaged, houses and farms burnt and destroyed. Upon this sight, we took some Norse women and children with us and fled far into the fjord. And there they remained in peace for many years, taking the Norse women into marriage.”

In his infamous A Description of Greenland Egede makes a different claim: the Norse people were destroyed by the Inuit population. Modern research is sceptical of both accounts. Archaeologists have combed through Norse ruins and found no sign of large-scale violent destruction. For this reason, historians generally think that attacks from the sea may not be the primary reason for the colony’s demise — but repeated raids certainly didn’t help.

So what happened? Some blame a colder climate ushered in by the end of the Medieval Warm Period. Colder temperatures meant it was harder to produce hay, which saw more animals go hungry. Worse still, the ship lanes surrounding Greenland’s settlements became clogged with ice. While researchers now think that the colonists were more self-sufficient than first thought, fewer ships was bad news for settlements mostly reliant on imports.

The Greenlanders sold walrus ivory in return for the goods that kept the colony afloat, which supplied elites across Europe with ivory crucifixes, knife handles, and jewellery. While Greenland had become a major supplier of ivory to the continent by 1100, prices for walrus teeth may have fallen after 1350 as Asian and East African markets began to provide elephant tusks.

Jared Diamond, author of the much loved (and much maligned) Guns, Germs and Steel, said of the Norse colonists that “every one of them ended up dead.” But as Robert Rix, author of the wonderful The Vanished Settlers of Greenland, argues: “It is more plausible that the dwindling possibilities in Greenland, aggravated by pirate raids and other factors, drove a constant emigration back to Iceland and Norway.”

Under the ice

Like the legends of the Atlantis of the Sands in the Arabian Peninsula or the Lost City of Z in South America, 19th and 20th century Europe was gripped by tales of rich cities lost in time. In the case of Greenland, they had good reason to be.

Ivar Bardarson, a fourteenth-century Norwegian clergyman, journeyed to Greenland before contact was lost with the colony. In his reports, Bardarson described church buildings, bays for catching whales, fishing lakes, polar bears, reindeer, ivory, and hot springs with healing properties. He also mentions rich vegetation and fields of wheat.

Little of this was true, but reports such as these fuelled beliefs that there must be wealthy settlements somewhere on the island. Hundreds of years later, when Hans Egede described the ruins of old stone buildings on the west coast, he had no idea that they were all that remained of the storied Eastern Settlement.

Soon enough, island and colony both were on the mind of British explorers. In the introduction to an English translation of Egede’s A Description of Greenland, an anonymous author writing in 1818 said the lost colony was a prize worth chasing for the British Empire:

“May we hope that the execution of this project [saving the Greenland colonists], which is prompted, not only by curiosity but by philanthropy, is reserved for the present era, and that it will be finally accomplished by the nautical skill and enterprise of this country!”

The writing coincided with a newfound interest in Arctic exploration, as British explorers searched for the Northwest Passage that would allow them to transport goods to and from Asia. The North Pole began to occupy the imagination of the European powers, with books like Mary Shelley’s 1818 masterwork Frankenstein confirming the top of the world as a place of mystery, heroism, and adventure.

Other stories, like The Surpassing Adventures of Allan Gordon from 1837 by the Scottish author James Hogg, entrenched the lost colony of Greenland in the public consciousness. In the book, apprentice Allan Gordon joins a whaling ship bound for Greenland. After the ship is crushed by ice, Gordon becomes the sole survivor and discovers the lost Norse colony. Much carnage ensues, but he ultimately makes it back to Scotland.

But it wasn’t just the British who sought a frozen Shangri-La. The American writer Fitzhugh Green’s 1924 novel ZR Wins told a story about the lost colonists, who now inhabited a secret land in the Arctic. Green also wrote non-fiction. As the United States flew an airship over the North Pole, he speculated that it may find nothing less than a “vast continent heated by subterranean fires, and inhabited by the descendants of the last Norwegian colony of Greenland!”

The idea seems risible to the modern reader, but there was some method behind the madness. After all, the Arctic received months of continuous sunlight in summer, its deep ocean was thought to prevent freezing, and warm currents were observed flowing north of Greenland. Albert Sidney Morton's Beyond the Palaeocrystic Sea from 1895 imagined places like Nikiva, a city on an island in the Polar Sea with average temperatures of 16°C or 60°F.

But the colony, as we know, was nowhere to be found. The Norse Greenlanders likely went home because the environment would not cooperate. Almost 500 years later, the same thing happened again.

The lost city

Greenland’s territory was confirmed as a single entity in 1933 when an international tribunal decided that the whole island belonged to the Danish crown — and not to Norway. As Arngrímur Jónsson, an Icelandic writer, explained: ‘Greenland was once governed by, and paid taxes to, Norway, and subsequently to the Danish kings, when the Norwegian realm was ceded to Denmark.’ When Norway split from Denmark in 1814, Greenland remained with the Danes. All the while, richer suitors looked on.

In 1867, following the Alaska Purchase, the US had reportedly ‘nearly completed’ a deal for the island that never materialised. In 1910 the US and Denmark explored a merry-go-round trade deal involving German possessions in Europe and the Philippines islands of Mindanao and Palawan. After the Second World War Denmark rejected another cash offer for the island. And in 1955 President Eisenhower, just a few years after signing a major treaty with Denmark about the defence of Greenland, reportedly mulled a new offer.

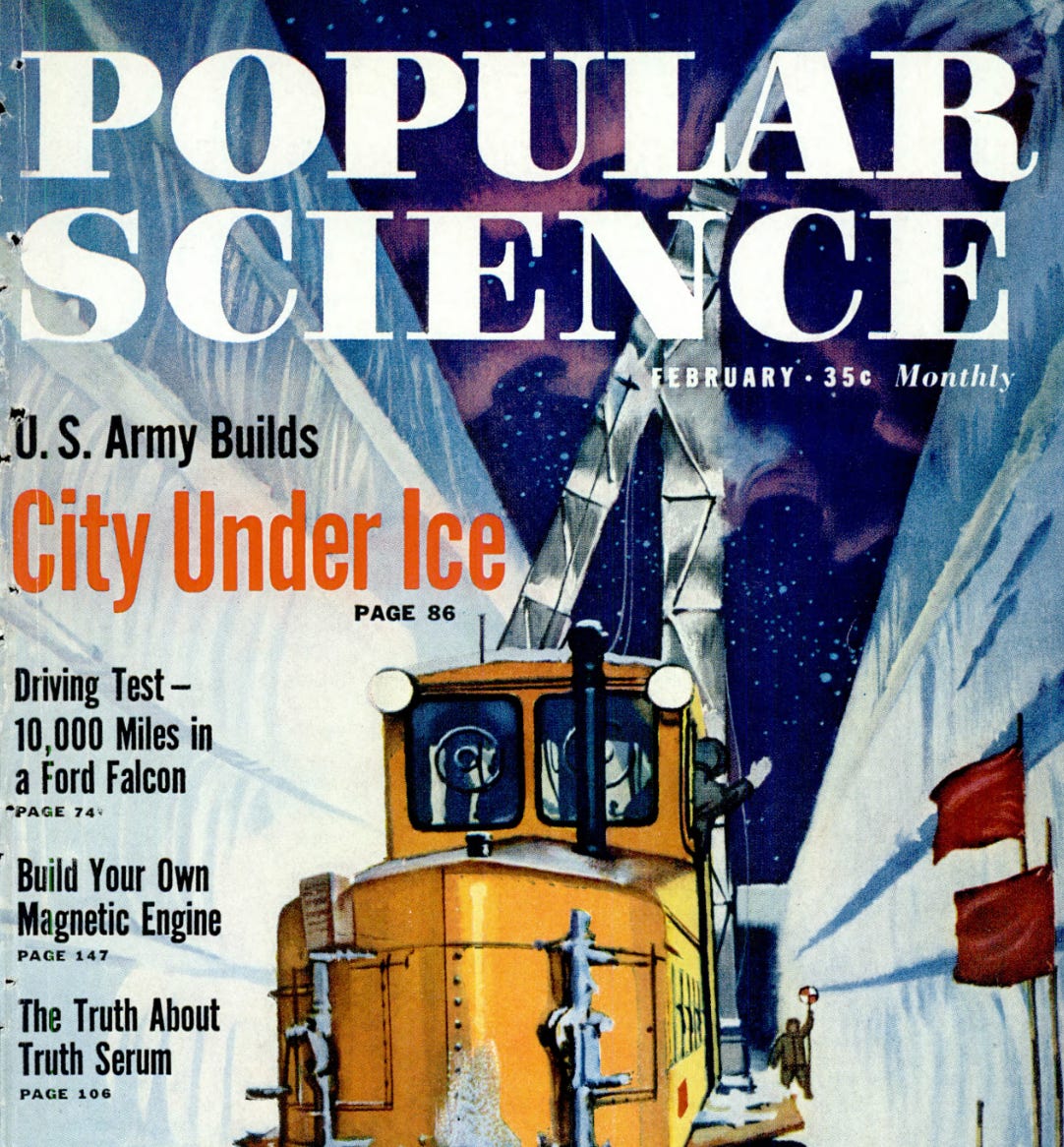

Five years later, resigned to cooperation, the Kennedy administration hatched a new plan. A 1960 issue of Popular Science described a startling new project for readers:

“The strangest boom town in the world is being built by Army engineers under Greenland's vast icecap. Completely hidden by snow, it will be powered by atomic energy—and will be about as safe a place as you could find in case of atomic attack. It would be hard for an enemy to find; and snow would absorb much of the shock of an atomic blast, and partially shield the occupants from radiation and fallout.”

Known as Camp Century, it was the stuff of pulp science fiction. The site consisted of a web of trenches dug into the ice, with each trench twenty-six feet wide and twenty-six feet deep. On top of these the US Army dropped a mosaic of ready made buildings. Powering the base was a portable nuclear reactor that the military shipped from the United States and dragged out across the ice sheet.

“Building Camp Century,” as physicist Adam Frank put it in Light of the Stars, “required a monumental effort, but one that would achieve a monumental breakthrough.” Like something you might find on an oil rig, the engineers built drills that churned through almost a mile of ice. The slab covering Greenland is the sum of snowfall, with each layer of frost resting on top of another. Over the eons, they formed a well of chemical markers containing clues about the planet’s past.

Using this data, the camp’s researchers found that around twelve thousand years ago global temperatures plummeted. In a matter of decades, average temperatures had dropped by five degrees Fahrenheit in some places — and as much as twenty-seven degrees in others. The findings shattered the assumption that climactic changed occurred gradually over very long periods. It could happen fast. Not over millennia, but decades.

But Camp Century wasn’t built to extract ice cores. The base was part of Project Iceworm, a defunct Cold War initiative to construct a network of nuclear missiles beneath the Greenland ice sheet. The plan envisioned up to 600 Iceman medium-range ballistic missiles deployed across a 52,000-square-mile network of tunnels and bunkers. Had it come to fruition, it would have required 11,000 personnel to operate.

The plan was abandoned when engineers found that the ice sheet's natural movement rendered the tunnel structures unstable. Today, the remains of Camp Century wait silently underground. The University of Colorado Boulder estimate that tonnes of hazardous waste were left behind, including 53,000 gallons of diesel fuel and 63,000 gallons of wastewater.

Last year, a flight using a NASA-built radar scanned what was left of Camp Century. While the base had been detected by other surveys, the 2024 mission generated a more detailed map than previous flyovers. This assessment didn’t tell us anything new, but it did remind us that the bones of Camp Century still lie in state.

“There is nothing so artistic as a haze.” That was the conclusion of Arthur Conan Doyle, when he reflected on the fate of the lost colony after the whaler returned safely to port. For the ghosts of Greenland, ice is something like haze set solid. It records the rhythms of ages past and preserves the residue of peoples long gone. It makes tombs of steel, concrete, diesel, and sewage.

Ice keeps the score. It reminds us that every political project is subject to forces greater than us, that each layer of the past writes its own history. The snow keeps falling and the frost gets thicker. What are we building that will be found, after we are gone, by those who no longer understand what we were doing?

I listened to the appropriately named Under the Ice by The Drums as I wrote this essay. Check it out here for a nicely shaped pre-post-punk revival artefact.