“If any love magic, he is most impious:

Him I cut off, who turn his world to straw”

— Fragment of a poem written by Walter Pitts to Warren McCulloch

Walter Pitts was born in Detroit in 1923. His father was a boiler-maker, and by all accounts a violent man who pressured the young Pitts to pack in his studies and get a job. Defying his father, Pitts spent his free time at the local library where he read widely about mathematics, science, philosophy, and history.

He read Bertrand Russell’s Principia Mathematica, found mistakes, and wrote to the Welsh mathematician to point them out. According to later tellings, Russell was impressed and even invited Pitts to journey to Cambridge to study with him. Still a twelve-year old boy at this point, Pitts was glad to receive the offer but turned it down on account of his age.

But three years later, when he heard that Russell would be visiting the University of Chicago, the fifteen-year-old ran away from home and headed for Illinois. He landed in Chicago, where he supported himself with menial jobs while joining those lectures he could.

Pitts never enrolled but attached himself to the orbit of Chicago’s intellectuals, publishing his first paper in 1942 when he was eighteen. His ‘Some Observations on the Simple Neuron Circuit’ appeared in the Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, which was the main venue for early attempts to model biological and cognitive processes with mathematics.

The journal was headed by Nicolas Rashevsky, a Russian-born researcher best known for work rendering neurons in the language of mathematics. Rashevsky vouched for Pitts and allowed him to publish under the University of Chicago banner, despite the fact that Pitts had no formal ties to the institution.

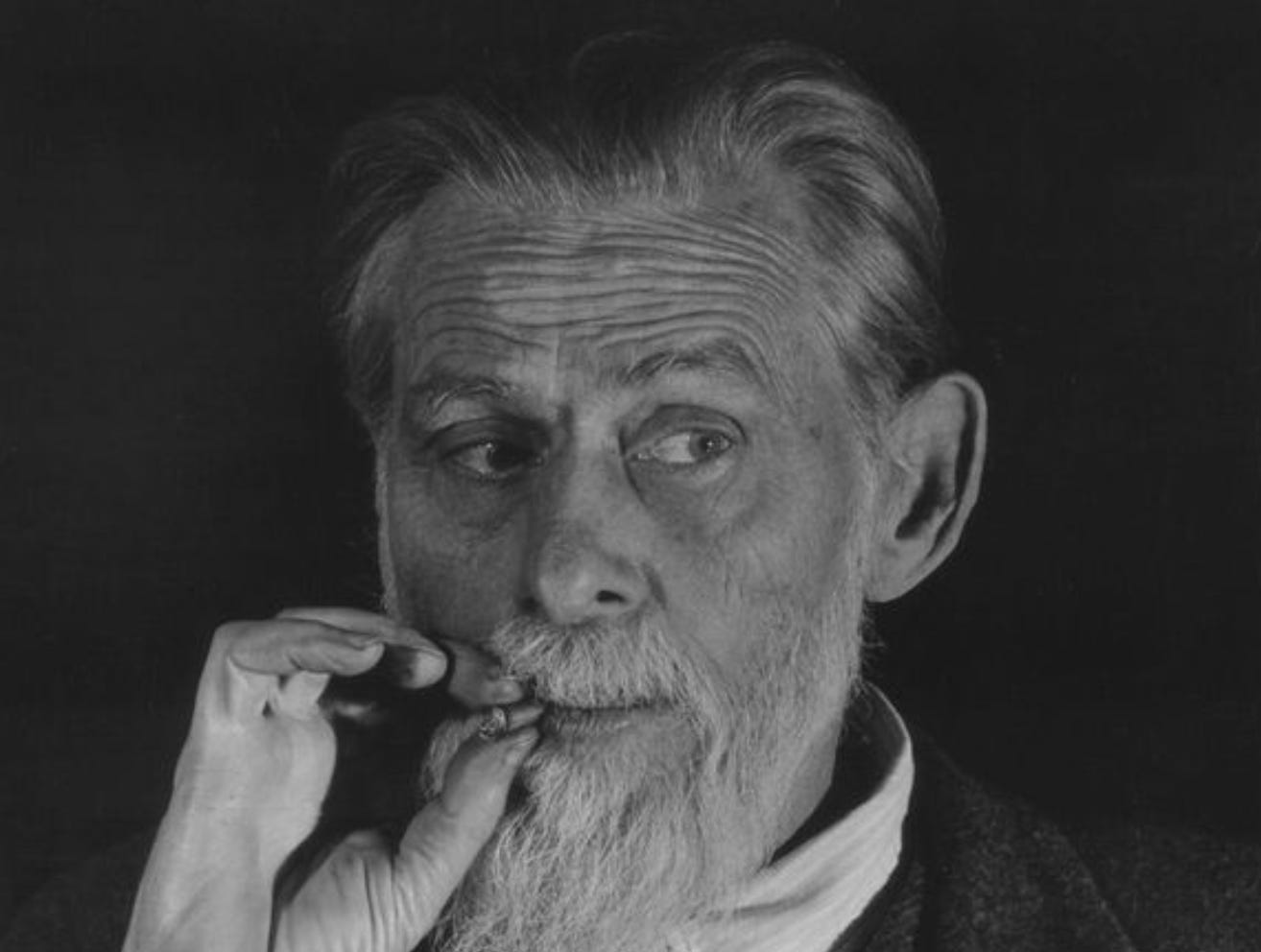

Warren McCulloch lived a very different life, born a generation earlier into an East Coast family of lawyers, theologians, and doctors. McCulloch studied mathematics at Haverford, philosophy and psychology at Yale, then medicine at Columbia. By the 1940s he was working as a neuropsychiatrist in Chicago. He wrote poetry, smoked heavily, and liked staying up past four in the morning with whiskey and ice cream.

The two men met in 1942 through Jerome Lettvin, a medical student who Pitts got to know at one of Russell’s lectures at the university. Pitts was eighteen and McCulloch forty-three. They recognised each other immediately through a shared enthusiasm for Gottfried Leibniz, the 17th century philosopher who wondered whether human thought could be represented an alphabet composed of signs and symbols.

McCulloch, who was looking for a mechanical account of mind, had been trying to model neurons in a kind of Leibnizian language but lacked the mathematical prowess to do so. In Pitts, he saw someone who might be able to help, and invited him to live with his family in the Hinsdale suburb of Chicago. For Pitts it became a surrogate home, a place that he would remember fondly for the rest of his life.

Logical calculus

Pitts and McCulloch wanted to use Leibniz’s calculus of thought as the basis for understanding neural activity. In 1943 the pair published their joint paper, ‘A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity,’ in Rashevsky’s Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics.

They proposed a simple model in which each neuron acted as a binary unit, firing if its inputs crossed a threshold (or remaining silent otherwise). By connecting these units together in different ways, they demonstrated how some basic logical operations Leibniz had described — AND, OR, and NOT — could be carried out by networks of neurons. From this starting point they argued that more complex statements could be built, and that any proposition in logic could, at least in principle, be represented in a network.

The force of the paper lay less in its biological plausibility than in its commensurability. To physiologists, it offered a stripped-down account of nervous activity. To logicians, it showed how propositions could be built into circuits. To mathematicians and engineers, it looked like a schematic for machine design.

In 1943 Jerome Lettvin introduced Pitts to Norbert Wiener, the computer scientist best known for pioneering the field of cybernetics. Wiener was impressed with Pitts, later writing that he was “without question the strongest young scientist I have ever met”. He went on to promise Pitts a doctorate in mathematics at MIT, despite the fact the young man lacked a high school diploma.

Pitts soon moved to Cambridge as Wiener’s protégé. He joined a circle that included John von Neumann, who in 1945 wrote the ‘First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC’. It was a foundational document for modern computer architecture, one that cited only a single scientific paper: McCulloch and Pitts’s ‘A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity.’

McCulloch followed Pitts to Massachusetts in 1952, when MIT’s Jerome Wiesner invited him to head a new project at the Research Laboratory of Electronics. He accepted, trading his professorship and suburban house in Chicago for an apartment and the chance to work again with Pitts. Alongside Lettvin and the Chilean biologist Humberto Maturana they established an ‘experimental epistemology’ group in Building 20, a makeshift wartime structure that became famous as an incubator of ideas.

McCulloch and Pitts had gone from Chicago salons to the centre of American science, with their work standing at the junction of psychiatry, biology, mathematics, and engineering. The field of cybernetics was born from the convergence, with Wiener at its head and McCulloch and Pitts among its central figures.

Just as things seemed to fall into place, the good times came to an abrupt end when Wiener’s wife told him that McCulloch was romantically involved with their daughters. Historians generally think there was no evidence for the story, but Wiener believed it all the same.

He sent Jerome Wiesner, then associate director of the Research Laboratory of Electronics, a telegram: “Please inform Pitts and Lettvin that all connection between me and your projects is permanently abolished. They are your problem.” He never spoke to Pitts again, and never explained why.

For Pitts, it was devastating. He had grown up with an abusive father, cut off his family at fifteen, and been taken in by McCulloch as a surrogate son. Wiener had been another father figure, a mentor who recognised his genius and placed him at the centre of American science. He turned down the doctorate that MIT had offered him and set fire to his dissertation notes. He withdrew from friends, drank heavily, and began a long retreat into obscurity.

In the years after the break Pitts still worked, though without the same momentum that defined his early years. With McCulloch, Lettvin, and Humberto Maturana he co-authored ‘What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain’ (1959), an experiment that found the eye filtered and pre-processed visual information before passing it on to the brain. The work was important, but for Pitts it was unsettling because it punctured his view of the brain as a hierarchy of logical propositions.

In 1969, aged 46, Pitts died from complications of cirrhosis of the liver in a boarding house. Four months later McCulloch, weakened by a heart attack, also passed away.

McCulloch and Pitts are remembered almost entirely as forerunners of the connectionist tradition, the people who first showed that networks of neurons could compute. But in 1943 they didn’t think they were choosing between logic and learning. They felt they had squared the circle by demonstrating that what Leibniz had imagined as a calculus of propositions could be realised in the firing of neurons.

Their story reminds us that AI likes to take the shape of its container. In the early 1940s, psychiatrists could look at the logical neuron and see a stripped-down account of nervous activity, logicians could look at it and see the possibility of a calculus of thought, and engineers could look at it and see a schematic for machine design. The commensurability made possible by a single model allowed these groups to talk to one another, even as they pursued very different ends.

"The work was important, but for Pitts it was unsettling because it punctured his view of the brain as a hierarchy of logical propositions."

That's interesting to me, because the visual system (in the standard account anyway) is at least a bit like a hierarchy of propositions; contrast detectors build up into edge detectors, edge detectors build up into shape detectors, and so on. That paper even identifies fly detectors, which more or less signal the proposition "there is a fly in this part of the visual field".

I wonder what kind of results Pitts had in mind, if this was insufficiently propositional?