I write for a living. I write as an academic, I write as a researcher, and I write as a blogger. I’m writing my way through a PhD and I’m writing a book thanks to the generosity of the good people at Emergent Ventures.

I write for myself and I write for other people. I write to understand and I write because I enjoy it. I write when I’m happy but rarely when I’m miserable.

The things I type into a computer are chum for AI. I don’t write using language models, but I don’t begrudge those who do. I feel no sense of antagonism towards the technology or the organisations building it. Maybe that’s because I used to work for one of them.

Or maybe I’m ambivalent on more selfish grounds. Language models have been spitting out perfectly acceptable copy for quite some time. GPT-4.5, released in February, was the first model to make me laugh.

AI will keep improving. One day soon it will be technically superior to better writers than me. But I don’t expect it to put me out of a job when that happens.

Let’s assume that models continue to improve, that the line keeps going up and to the right. Imagine they can neatly perform all the little tasks that make up many of the professions in the creative industries.

In this world, AI is both capable of producing hyper-personalised content for the individual and interpolating between preferences to produce a golden age of Netflix slop. Some of it is good, some of it is bad, but there is something for everyone.

But in our imaginary universe, I suspect that humans will not be so easily out-muscled in the creative arena. In art as in life, people like different things. Taste is the currency of the artistic world.

I wrote about this idea last month. The basic argument is that AI slop is the price we pay for creative abundance. It’s a byproduct caused by reconfiguring the means of creative production, a kind of friction produced by the collision of large models and the arts.

Some people liked it and others really didn’t. A couple of people thought I was advocating slop for its own sake. Others gave some interesting rebuttals, pointing out that it didn’t really grapple with what it is to appreciate art.

For my money, appreciating art (or consuming slop) is basically about two things: the formal and the contextual. The former deals with technical and compositional elements (in painting, things like line, colour, shapes, and texture) while the latter is about situating art within various frameworks (phenomenological, semiotic, historical etc.) for meaning-making.

These ideas are useful for understanding the allergic reaction that many people have to AI art. Even if the formal elements look good, they argue, it doesn’t contain any deeper meaning because its creation is divorced from a proper artistic context.

The obvious problem with this line of thinking is that AI art is ripe for contextual analysis. It’s the product of giant datasets, billions of dollars of training compute, and the mechanically reconstituted guts of the internet. An AI art exhibition would be an excellent vehicle for getting under the skin of corporate power.

But contextual analysis has its limits. Call me a rube, but when I go to the cinema I find a film’s aesthetic experience matters at least as much as its contextual determinants. The visual economy, the performances, and the characterisation are the things that I’m interested in.

I mention cinema because it reminds us that formal appreciation isn’t just some shallow pursuit of visual splendour. Yes, the miasma in which a film was produced is important, but movies are perfectly capable of supporting themselves as independent creative artefacts.

I think about this idea as a sort of creative functionalism. In the philosophy of mind, functionalism is the idea that consciousness is a function of what a system does, not what it is made of. The functional role of mental states is more important than their physical implementation.

Creative functionalism holds that the thing that matters most is good art, not the process by which it came into being. How the cake is baked is less important than what it tastes like.

We are of course on slippery ground here. I’m not suggesting that we ignore context or that it is even possible to do so. What I am saying is that, when I weigh the formal against the contextual, I generally find the former more relevant than the latter. I’m with Dewey on that one.

The first time I listened to Bach’s Air on the G String I was mesmerised. Then I read about how the violinist August Wilhelmj tinkered with the original and liked it even more. But if I hadn’t known that I still would have loved it because I don’t think meaning is simply a product of authorial intent.

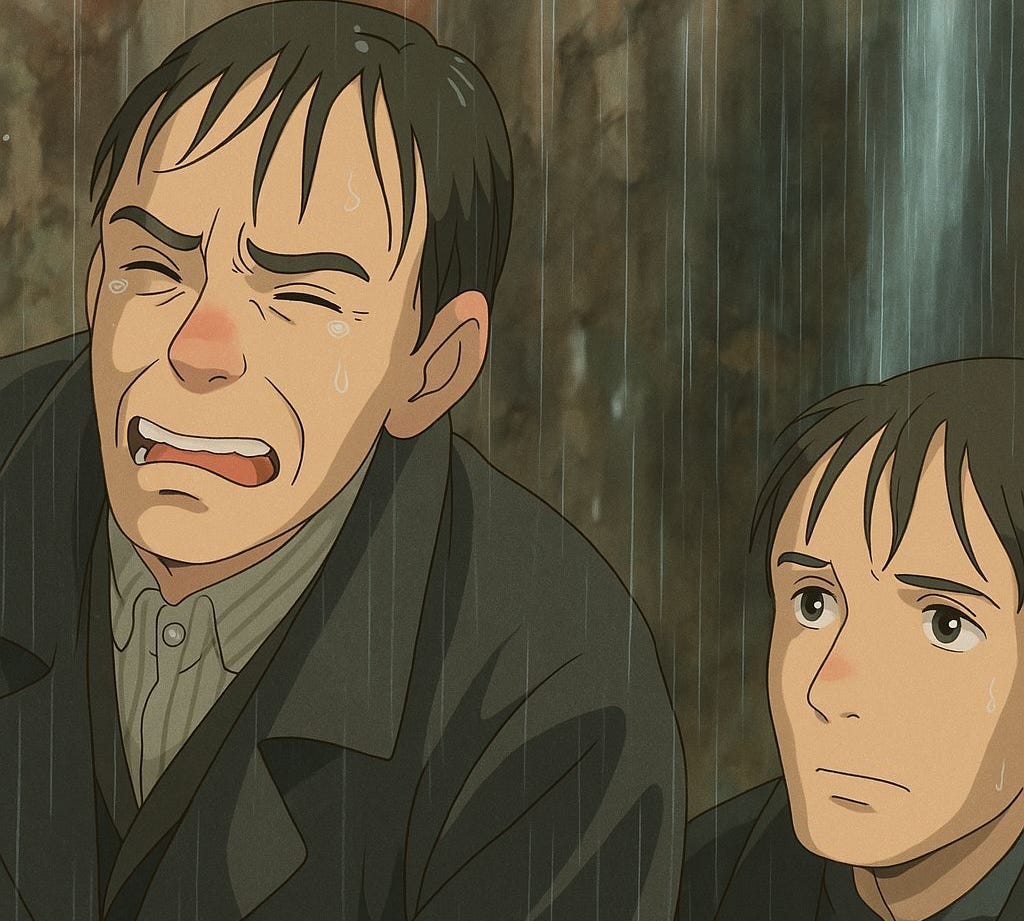

Ghiblification

Most of you will have seen a Studio Ghibli meme somewhere this week. For those who didn’t: OpenAI released a new image generation model, which proved to be much better than previous efforts. It can render stuff in more detail, produce higher fidelity outputs, and can copy styles to a tee.

That last point is the important one. Posters quickly landed on Studio Ghibli as the aesthetic of choice. Soon everything was Ghibli. Name a famous meme. That’s Ghibli now. An iconic image from history? That’s Ghibli. Your friends’ holiday pictures? Ghiblified.

Mercifully or regrettably (delete as appropriate) Ghiblification is already running its course. It will surprise exactly no one to learn that there can in fact be too much of a good thing.

In some ways we’re looking at a very modern tragedy of the commons. It’s fun to generate Ghibli memes, but it’s quite possible that in doing so you’re siphoning off a little bit of magic. I’m not sure I feel that way right now, but maybe I will when I next watch Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

Of course, the Studio Ghibli catalogue is right there. It hasn’t gone anywhere. When you complete a paint-by-number kit of the Mona Lisa, the original doesn’t drop from the wall of the Louvre.

Obviously some people will always prefer the human touch. The question is how many. It might be that human-made artefacts become something like digital handicrafts, a new type of cottage industry for a slice of society who like their art the old fashioned way.

But I doubt it. My intuition is that demand for human creative output isn’t going to fall off a cliff. It comes down to why someone engages with creative life. Some people might only care about the artist, others only the art.

But we know that appreciating art is about taste. That means that over the long run, barring some sort of dramatic change in human nature, there will always be interest in people making stuff. Not in every instance, I’m sure, but more than enough to nip the emerging moral panic in the bud.

It’s easy to hate AI art. Encouraged even. It is table stakes to say that AI can’t make art, and anyone who touches an image generator has committed an act of cultural vandalism. The sociology of the thing is curious. It’s satisfying to think of oneself as a truth-to-power speaking maverick, especially when everyone agrees with you.

Partly it’s because no one wants to be seen to be shilling for trillion-dollar companies. That’s understandable, but I doubt much will change for the open source image generation tool released for free by the indie hacker.

Werner Herzog said “Academia is the death of cinema. It is the very opposite of passion. Film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates.” It’s a nice sentiment. After all, the purist would say anyone using AI should read the room.