Despite major improvements in capabilities, the deployment of systems that boast millions of users, and an outsized role in minting a new trillion dollar company, AI isn’t top of the agenda for most leading political figures (though President Trump has been mentioning the need to dramatically boost US energy production to support American AI ambitions).

In a tour of Silicon Valley, former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair said this week that AI (and a cluster of similarly promising technologies) represented the single most important issue facing the world. He would, were he to have his time again, build a political programme designed to harness AI in service of a richer, healthier, and better educated society. By the time the next electoral cycle rolls around, I wonder if the rest of the political class will feel the same way.

Back in the present, this edition has research showing that LLMs are sensitive to demographic factors like education level and inferred English proficiency, a history of the ELIZA chatbot seeking to add some much needed context around the “precursor to ChatGPT”, and a study confirming that universities are not equipped for detecting AI generated content.

Three things

1. Demonstrating demographic discrimination

Large language models are mirrors. We know that they reflect the views of their creators (through specific design choices via mechanisms like RLHF and system prompts) and the underlying datasets on which they were trained. We also know that they are sensitive to user prompts, and that a better prompt means a better response (garbage in, garbage out and all that). This sensitivity is useful, especially for developers toying with the introduction of personalisation mechanisms.

But dynamic systems pose challenges. According to a new study from MIT researchers, popular LLMs are sensitive to demographic factors like education level and inferred English proficiency. The group wrote fictional bios for users based on these differences, which they used to test GPT4, Llama, and Claude on benchmarks used to measure accuracy and factualness. The experiment found “a significant reduction in information accuracy targeted towards non-native English speakers, users with less formal education, and those originating from outside the US.”

Aside from the obvious problems this dynamic draws into focus, the report reminds me of the ‘looping effect’ phenomenon whereby ‘labelling’ a person in a particular way changes their behaviour, beliefs or perspectives. In the canonical example of this effect, a patient incorrectly diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder can start displaying traits of a condition that they do not have.

The upshot is that repeated use of AI may—in the maximalist version of this story—actively mould personal behaviour based on some account of who the system thinks you are. In a world where AI becomes deeply entwined with your personal and professional lives, the ability for you to tell a system about the type of person you are (or want to be) will be essential for persevering personal autonomy.

2. Why, why, why, ELIZA?

Much ink has been spilled trying to explain where the likes of ChatGPT and Gemini came from. One common mechanism for doing that, which mostly leaves the history of AI to one side, involves centering the story behind the form factor of the technology: the chatbot.

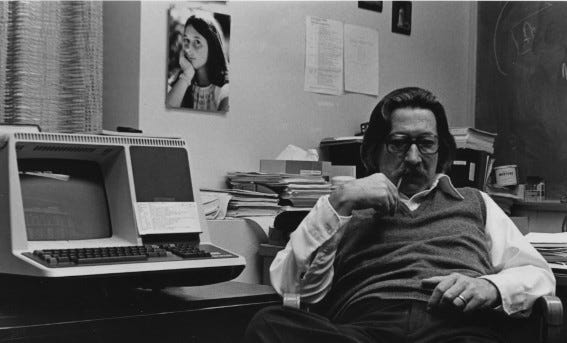

These accounts often tell us about ELIZA, an early natural language processing computer system developed from 1964 to 1967 at MIT by Joseph Weizenbaum. The most famous function of the system simulated a medical professional belonging to the Rogerian school of psychotherapy in which a therapist listens to a patient and reflects their words back to them.

Instead of connecting ELIZA to today’s systems, Jeff Shrager of Stanford University looks at the underlying technical contingencies that contributed to the system’s development and its “accidental escape” into the world.

First, it begins with the genesis of ELIZA, explaining that Weizenbaum built the system to study conversations between humans and machines. It shows that Weizenbaum picked a Rogerian psychotherapist because it provided the illusion of understanding by offering a context wherein simple parroting behaviour wouldn’t seem out of place.

Second, the paper takes us on a whistle-stop tour of computing history from Ada Lovelace to John von Neumann via Alan Turing and Kurt Godel. It argues that ELIZA was a natural outgrowth of Weizenbaum’s 1963 SLIP programming initiative, which would introduce a “symbol manipulator for the use of behavioral scientists.”

Third, it argues that ELIZA found fame when a colleague of Weizenbaum’s coded a version of the system using the popular LISP programming language, which in turn found its way into the hands of AI enthusiasts via the proto-internet platform ARPANet.

To summarise: ELIZA was not built as a chatbot, its creator deliberately designed it to provide the illusion of intelligence, and it was misinterpreted by the fledgling computing community after it escaped containment via ARPANet. Funny old world!

3. AI detectors still don’t work

As I’ve written about many times, young people are (unsurprisingly!) adopting AI at a significantly faster rate than their older counterparts. They are using AI at school or university, which has provoked much consternation from those worried about the integrity of the education system. The introduction of AI has also seen some teachers wrongly accuse students of cheating based on misconceptions about the validity of ‘AI detectors’ whose extreme rates of false positives mean the technology currently causes far more harm than good.

Now, new research from the University of Reading confirms that educational institutions are not equipped for detecting AI generated content. As they explain: “We report a rigorous, blind study in which we injected 100% AI written submissions into the examinations system in five undergraduate modules, across all years of study, for a BSc degree in Psychology at a reputable UK university. We found that 94% of our AI submissions were undetected.”

Ultimately, as the authors suggest, the use of AI in education is here to stay. Students will keep using ChatGPT and other systems like it, and teachers will need to find ways to accommodate usage in a manner that allows them to accurately assess pupils. Even up-weighting the role of supervised exams, universities will need to identify mechanisms for assessing pupils that don’t rely solely on in person tests (there is, after all, a reason independent coursework exists in the first place).

To do that, schools may have to move away from testing writing ability and towards evaluating higher-order thinking skills, creativity, and application of knowledge in ways that are challenging to fully outsource to AI. Adopting process-oriented grading models (with more weight on drafts, outlines, and revisions) and assessing the communication of knowledge (via group projects, presentations and oral assessments) could be a good place to start.

Best of the rest

Friday 28 June

Carl Shulman on the economy and national security after AGI (80,000 Hours)

Finding GPT-4’s mistakes with GPT-4 (OpenAI)

Computational Life: How Well-formed, Self-replicating Programs Emerge from Simple Interaction (arXiv)

Google launches Gemma 2, its next generation of open models (Google)

Zuckerberg disses closed-source AI competitors as trying to 'create God' (TechCrunch)

How to predict AI wrong (Vox)

Strategic Content Partnership with TIME (OpenAI)

Thursday 27 June

Commodification of Compute (arXiv)

AI incident reporting: Addressing a gap in the UK’s regulation of AI (CLTR)

Fairness and Bias in Multimodal AI: A Survey (arXiv)

Expanding access to Claude for government (Anthropic)

Predicting AI’s Impact on Work (GovAI)

Training AI music models is about to get very expensive (MIT Tech Review)

AI, data governance and privacy (OECD)

Wednesday 26 June

The Multilingual Alignment Prism: Aligning Global and Local Preferences to Reduce Harm (arXiv)

Meta is planning to use your Facebook and Instagram posts to train AI - and not everyone can opt out (Sky News)

Coordinated Disclosure of Dual-Use Capabilities: An Early Warning System for Advanced AI (IAPS)

The A.I. Boom Has an Unlikely Early Winner: Wonky Consultants (NYT)

How OpenAI Leaving China Will Reshape the Country's AI Scene (TIME)

Dwarkesh Patel interviews Tony Blair (X)

Tuesday 25 June

Naturalizing relevance realization: why agency and cognition are fundamentally not computational (Fronties)

Sir Patrick Vallance: "If you're a regulator, the incentive to take risks is virtually zero" (Substack)

In the Race to Artificial General Intelligence, Where’s the Finish Line? (Scientific American)

OpenAI Delays Launch of Voice Assistant to Address Safety Issues (Bloomberg)

Monday 24 June

Large Language Models Assume People are More Rational than We Really are (arXiv)

Major Labels Sue AI Firms Suno and Udio for Alleged Copyright Infringement (Billboard)

Does Cross-Cultural Alignment Change the Commonsense Morality of Language Models? (arXiv)

Intelligence Explosion does NOT require AGI (X)

A Survey of Machine Learning Techniques for Improving Global Navigation Satellite Systems (arXiv)

ChatGPT still can't beat YouTube when it comes to getting answers (techradar)

New AI scorecard can assess strength of state, federal legislation (StateScoop)

Claude 3.5 suggests AI’s looming ubiquity could be a good thing (The Guardian)

Job picks

Some of the interesting (mostly) non-technical AI roles that I’ve seen advertised in the last week. As usual, it only includes new positions that have been posted since the last TWIE (but lots of the jobs from the previous edition are still open).

Senior AI Governance Researcher, Apollo Research (London)

Senior Director, Strategic Insights Analytics and AI, UK Government (London)

Security Operations Lead, xAI (US)

Senior Program Manager, Responsible AI, Microsoft (Seattle)

Predoctoral, Postdoctoral, Law Student Fellow, or Visiting Student Expression of Interest, Princeton (US)